TV | By Tony Maglio on April 26, 2016 @ 7:57 pm

In the new TV economy, broadcasters must fight for every last viewer. Who can count them?

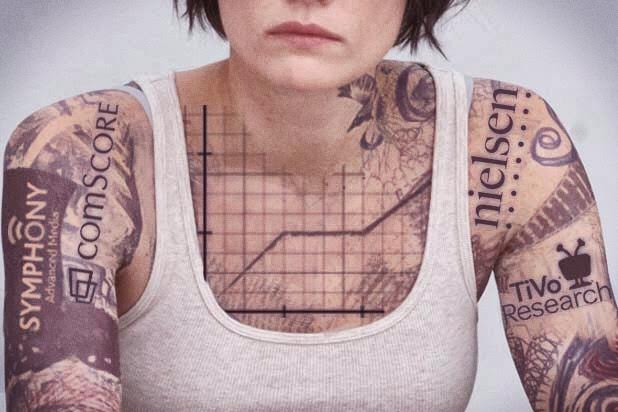

A battle is raging for the future of the television business as Nielsen, the standard-bearer for measuring audiences for 66 years, faces down a challenge from comScore, a data upstart that hopes to rule ratings in the digital age.

At stake is billions of dollars of TV and digital advertising. The company that wins a heated debate over how to count viewers in the age of DVRs, streaming and ad-blockers will wield enormous power among advertisers and an ever-widening pool of television programmers.

Television networks have long sought an alternative to the monopoly power of Nielsen, but while they embrace comScore as a challenger, they are unsure it can deliver on its promise to broaden their audiences.

Little wonder, then, that the tension was high at a New York trade show earlier this month when top Nielsen executive Kelly Abcarian found herself on stage with comScore’s chief product officer Manish Bhatia.

After a tense exchange over whose system worked better, Bhatia alluded to a guideline that members of the media-measurement trade association “embrace” each other, and he jokingly asked her for a hug.

Unsmiling, she declined.

A lot has changed since TV executives woke up every day to the “overnights,” which provided early-morning results for the previous night’s prime-time shows. In a wildly fragmented media landscape, millions of viewers now watch on-demand programming on their computers and phones, and Nielsen is crunching data over three- and seven-day periods and longer.

And yet the networks are still not satisfied. Broadcasters and cable channels are struggling in the new TV economy, scrounging for every last viewer. And they insist that Nielsen is under-counting their true audiences by adhering to its continued focus on age and gender as well as its old ways of tabulating viewership. In addition to set-top boxes, in smaller markets the company still relies on those fabled paper TV diaries of select “Nielsen families.”

Networks charge that some shows are seriously under-counted as a result. “Blindspot,” NBC’s freshman drama about a mysterious tattooed woman, has performed well according to traditional Nielsen measures.

This season, the thriller has averaged about 7.5 million viewers the night it airs, with another 5.1 million watching later on DVRs. But the network claims at least 800,000 more viewers are watching, particularly via streaming on computers, tablets and mobile devices that’s proven harder for Nielsen to measure.

If true, that could mean tens of millions of dollars in lost ad revenue.

And ad revenue is Topic A in corner suites as the broadcast business enters another round of upfront negotiations this spring to sell bulk ad time. Last year’s upfront generated more than $8 billion in revenue for ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC and The CW.

But TV ad revenue has been stagnant, falling 0.6 percent last year to $79 billion – and digital ads are on track to surpass that figure for the first time this year.

And it doesn’t help that the industry can’t agree on how many people are watching its programming, particularly in individual local markets.

“Local people hate Nielsen … they have terrible methodologies,” said Jane Clarke, CEO of the Coalition for Innovative Media Measurement Coalition, a trade group for the ratings industry.

“It has a very antiquated way of actually doing what they do,” she said, noting how the set-top boxes transmit minute-by-minute tune-in habits back to the Nielsen command center, which then breaks down the data by viewer age, gender, race, economic class, and location. “Advertisers don’t want to continue to buy all their media based on age and gender.”

The recent challenge by upstarts like comScore is a “wild card” in an industry anxious for change, said Will Somers, the head of research at Fox Broadcasting Networks, which subscribes to both comScore and Nielsen.

That’s just for the moment, he said. Over time, there will be one winner and one loser. “I doubt there’s going to be multiple currencies,” he predicted. “I don’t really think the business can transact that way and I think it makes it difficult for everyone.”

THE HEAT IS ON

ComScore has spent years measuring online audiences. But after paying $732 million last year for the local measurement powerhouse Rentrak, which focuses heavily on legacy media such as TV, the company decided to expand its reach and mount a direct assault on Nielsen.

Last month, comScore delivered its first ratings across digital and TV platforms. “We believe that the future belongs to comScore,” comScore President Bill Livek told TheWrap.

Unlike Nielsen, which centers its data around age and gender, comScore provides much richer information, Livek maintained. Nielsen extrapolates its ratings from thousands of households that agree to have “people meters” measure their viewing habits. But comScore data comes from 40 million set-top boxes that cable operators include without most customers even knowing they’re there. ComScore combines that household data with demographic details about consumer behavior.

And comScore performs better in areas where Nielsen is weak, according to critics, including measurement of local markets, cross-platform viewing, behavioral consumption habits, and lower-rated networks.

“The other guys are currency around age and sex, we’re the currency around how people buy products,” he said. “You can target [ad buys] a whole lot better and more efficiently.”

However, comScore declined numerous requests for specific data, so direct comparisons are impossible. “We don’t generally share TV ratings publicly,” a company spokesman wrote in an email. “Our TV ratings are currently being enhanced with some cross-platform info, which are just starting to be released to clients.”

BLINDSPOTS

Of course, Nielsen has not sat back on its heels.

The ratings giant — with a $18.77 billion market cap, compared to comScore’s $1.18 billion — introduced its own cross-platform measurement tool last fall, called Total Audience, to supplement its survey of about 100,000 households (an increase from 40,000 a few years ago).

Abcarian said Nielsen’s new Total Audience Measurement package “is really taking that pain and frustration out” of measuring viewers, providing “complete and comprehensive” coverage across a variety of platforms. Nielsen now has the capacity to look at on-demand data for more than 50 networks, she said. She is also critical of comScore’s methodology, which she dismisses as “big data” that fails to capture what clients really want.

“Quantity is not the same as quality,” Abcarian said.

But the rollout of Total Audience has been slow, frustrating many TV executives, especially given the imperatives of today’s on-demand and streaming market.

And networks complain that Nielsen is consistently underestimating the audience for more youthful-skewing shows like NBC’s “Blindspot,” which averages a 3.3 rating in the 18-49 demographic, the category most advertisers care about, over the course of a week. “Blindspot” was the 14th highest-rated broadcast series on TV last fall, according to Nielsen, but the network believes it might rank even higher if all the streaming views were factored in.

But for all the complaints about Nielsen, the advertising community still relies on its data. Nielsen is still “one of the better research companies out there,” GroupM managing partner Lyle Schwartz told TheWrap, while noting that his firm “often” had “disagreements” over individual measurements. (It’s worth noting that GroupM is owned by WPP, which has a minority stake in comScore.)

‘STUCK WITH THESE GUYS’

In January, NBC’s Wurtzel endorsed comScore as an alternative to Nielsen — a vital thumbs-up from a widely watched industry pro. He also mentioned smaller players such as TiVo Research, Reality Mine and Symphony Advanced Media who are poised to challenge Nielsen.

Nielsen, said Wurtzel, is still “woefully inadequate.” But, he acknowledged, “We’re kind of stuck with these guys… That’s one of the reasons everyone’s so frustrated.”

David Poltrack, the veteran head of research at CBS, compared the current situation to trying to move to a new house while living in the old one.

The industry is living in Building 1, which they helped Nielsen build by subsidizing costs. It’s now showing signs of deterioration. Nielsen is saying they’ll build a new building, but while they do that, clients have to stay in the old building and pay very, very high rent there. Worse, the new building will charge even more.

“That is something that the industry cannot accept,” Poltrack said.

Meanwhile, competitors are moving into the neighborhood, increasing the urgency for Nielsen to upgrade its measurement tools. About 85 percent of the company’s revenues come from programmers, with the rest from media buyers, who tend to prefer more granular, drilled-down data about audiences.

Total Audience capabilities are available in the market today, Nielsen said — but the rollout has been limited so far. The company does not plan to release Total Audience figures until after this year’s upfronts, at the request of its network subscribers.

During its initial evaluation period, the company counted more than 50 networks for video-on-demand data, 25-plus clients for digital video data, and 15 media brands for text-based measurements. More than a dozen media makers are dabbling in Nielsen’s Digital Content Ratings, TheWrap has learned.

Both companies are essentially trying to do the same thing: Measure linear and streaming viewership, counting and packing every single tune-in across every single device into one digestible (and accurate) number. Oh, and they have to deliver that repeatedly, and in a timely manner.

The battle for domination of the ratings market has only just begun.